Jordan’s Principle

By putting the child’s needs as the priority, Jordan’s Principle calls on the government of first contact to pay for the services and seek reimbursement later so the child receives the services and does not get caught in government disputes.2

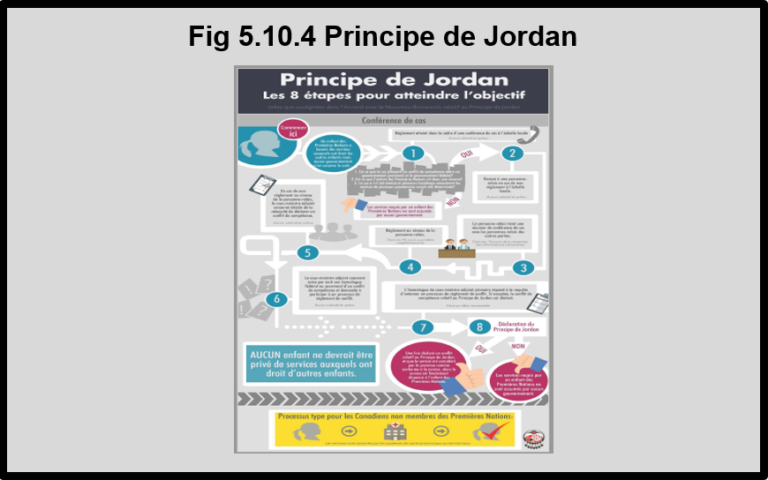

The infographic shown on this page, Jordan’s Principle: 8 Steps to Get There (as outlined in the New Brunswick Jordan’s Principle agreement) is a helpful tool to better understand and implement Jordan’s Principle. https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/JP%20Final%20with%20logo_AFN%20Graphic.pdf-accessed August 17, 2017.

Without denial, delay or disruption: Ensuring First Nations children’s access to equitable services through Jordan’s Principle, is a report developed by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), together with UNICEF Canada, The Canadian Paediatric Society, McGill University and the University of Michigan. The report highlights inequities experienced by First Nations children who need government services and how jurisdictional confusion among provincial, territorial and federal governments results in First Nations children being denied necessary care.3

1The Jordan’s Principle Working Group (2015) Without denial, delay, or disruption: Ensuring First Nations children’s access to equitable services through Jordan’s Principle. Ottawa, ON: Assembly of First Nations. http://health.afn.ca/uploads/files/jordans_principle_english.pdf-accessed August 17, 2017.

2First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada website. https://fncaringsociety.com/jordans-principle-accessed August 17, 2017.

3Assembly of First Nations. Press release. Without denial, delay or disruption: Ensuring First Nations children’s access to equitable services through Jordan’s Principle. http://www.afn.ca/en/jordans-principle-feb10-accessed August 17, 2017.

Adopted by the House of Commons in 2007, Jordan’s Principle is a child-first principle that puts the needs of the child first and foremost so they do not experience denials, delays, or disruptions in needed services due to jurisdictional disputes.1

Jordan’s Principle was named in memory of Jordan River Anderson, a First Nations child from Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. Jordan was born with complex medical needs and spent more than two years in hospital while the Province of Manitoba and the federal government debated over who should pay for his home care. Jordan died in the hospital at the age of five years old, never having spent a day in his family home.2

Responsibility for services to First Nations children is often shared by federal, provincial/ territorial and First Nations governments, resulting in a number of jurisdictional issues that can make access a challenge; in contrast, funding and delivery of these same services to most other children in Canada falls solely under provincial/territorial jurisdiction making access much less of an issue.1