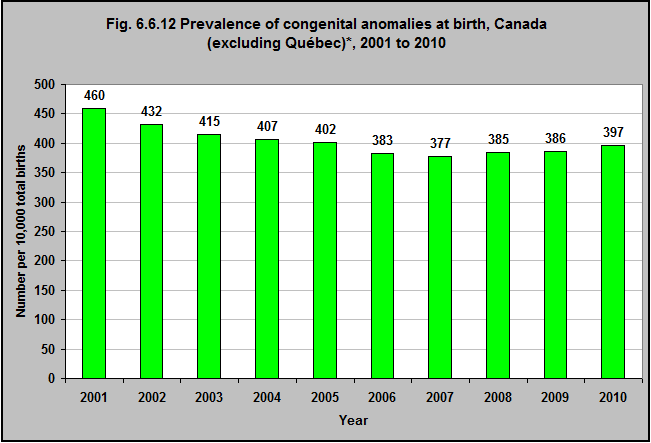

Prevalence of congenital anomalies at birth, Canada (excluding Québec), 2001 to 2010

Notes:

*Quebec does not contribute to the Discharge Abstract Database.

Source: CICH graphic created using data adapted from the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI), Discharge Abstract Database; and, Perinatal Health Indicators for Canada, 2013 http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/HP7-1-2013-eng.pdf – accessed May 22, 2017.

Congenital anomalies (birth defects) are the leading cause of death for babies under a year. They account for about a third of all infant deaths in Canada.1

In 2010, there were 11,441 babies born with congenital anomalies in Canada and the birth prevalence (number per 10,000 total births) of congenital anomalies was 397. The rate was 460 in 2001, and declined to 377 in 2007.2

1Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI), Discharge Abstract Database; and, Perinatal Health Indicators for Canada, 2013 http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/HP7-1-2013-eng.pdf– accessed May 22, 2017.

2Statistics Canada. Table 102-0562. Leading causes of death, infants, by sex, Canada. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1020562– accessed May 22, 2017.

Related Studies

There is a growing body of research examining the association between environmental exposures and congenital anomalies (birth defects). Several studies have found an increased risk for congenital anomalies in mothers who were exposed to organic solvents during pregnancy.3

For instance, an association was found between mothers’ and fathers’ exposure to pesticides – before and after conception – and their infants having – or dying from – congenital anomalies.4

However another study did not confirm this association.5

There have been a smaller number of studies of congenital anomalies and mothers’ exposure to air pollution prenatally. A recent pooled analysis of this research found associations between nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, particulate matter and certain cardiac anomalies.6

Over the last 25 years, research has found possible associations between mothers’ living near contaminated sites, hazardous waste sites or active facilities and congenital anomalies.4

3McMartin, K.I., M. Chu, E. Kopecky, T.R. Einarson, and G. Koren. 1998. Pregnancy outcome following maternal organic solvent exposure: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 34 (3):288-92. In Environmental Protection Agency. Children’s Health and the Environment Third Edition. 2013. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/ace3_2013.pdf – accessed May 22, 2017.

4Environmental Protection Agency. Children’s Health and the Environment Third Edition. 2013. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/ace3_2013.pdf – accessed May 22, 2017.

5Wigle, D.T., T.E. Arbuckle, M.C. Turner, A. Berube, Q. Yang, S. Liu, and D. Krewski. 2008. Epidemiologic evidence of relationships between reproductive and child health outcomes and environmental chemical contaminants. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews 11 (5-6):373-517. In Environmental Protection Agency. Children’s Health and the Environment Third Edition. 2013. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/ace3_2013.pdf – accessed May 22, 2017.

6Vrijheid, M., D. Martinez, S. Manzanares, P. Dadvand, A. Schembari, J. Rankin, and M. Nieuwenhuijsen. 2011. Ambient air pollution and risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives 119 (5):598-606. In Environmental Protection Agency. Children’s Health and the Environment Third Edition. 2013. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/ace3_2013.pdf – accessed May 22, 2017.