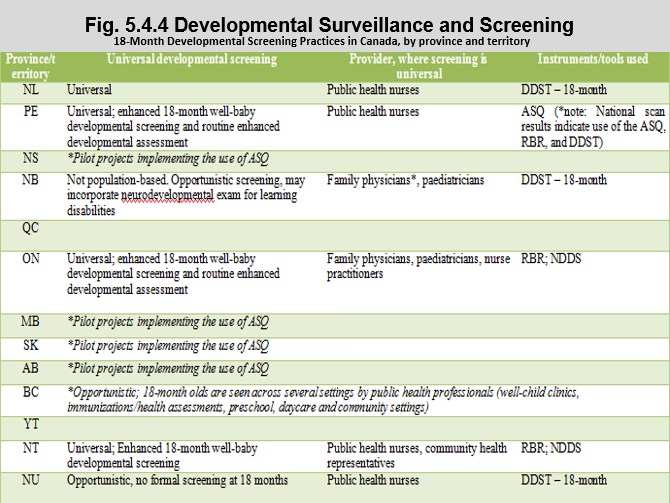

Developmental Surveillance and Screening – 18-Month Developmental Screening Practices in Canada, by province and territory

Notes:

ASQ: Ages and Stages Questionnaire; DDST: Denver Developmental Screening Test; NDDS: Nipissing District Developmental Screen; RBR: Rourke Baby Record.

Table used with permission from Guttmann, A., Gandhi, S., Hanvey, Li, P., Barwick, M., Cohen, E., Glazer, S., Reisman, J. & Brownell, M. (2017). Primary Health Care Services for Children and Youth in Canada: Access, Quality and Structure. In The Health of Canada’s Children and Youth: A CICH Profile. Retrieved from https://cichprofile.ca/module/3/ -accessed July 25, 2017.

Click here to see how the data was gathered.

The best approach to developmental surveillance and screening is not clear cut. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Canadian Paediatric Society have recommended routine developmental surveillance by primary care providers at all visits and the AAP guidelines recommend routine developmental screening tests be done at 9, 18 and 30-month visits.4

The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) has advocated for a universal visit using structured developmental assessment tools for all children at the 18-month well-baby visit. They recommend that an evidence-based supervision guide be used to monitor health, such as the Rourke Baby Record (RBR) and that a developmental screening tool (the most widely used are the Nipissing District Developmental Screen, ASQ, and PEDS/PEDS:DM) be used to stimulate discussion with parents about their child’s development.1

Six provinces and territories – Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland & Labrador, Nunavut, the Yukon and the Northwest Territories incorporate formal developmental surveillance or screening as part of an 18-month well-baby visit during routine visits, or around immunization schedules. There is variation in where the screening takes place, which health professionals do it, and the instruments used. Other jurisdictions provide targeted or opportunistic 18-month screening, often without use of formal screening tools. Only Ontario provides additional funding to primary care physicians for this enhanced visit.

4American Academy of Pediatrics. Identifying Infants and Young Children With Developmental Disorders in the Medical Home: An Algorithm for Developmental Surveillance and Screening. Policy Statement. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/118/1/405.full.pdf

Implications

Research shows that approximately one-third of Canadian kindergarten-age children fall short in at least one of the five areas of development: physical, social, emotional, language/cognitive or communication.1However, according to the Early Development Instrument (EDI), which is an assessment completed by kindergarten teachers in most provinces and territories, more than a quarter of Canadian children scored as ‘vulnerable’. This suggests that many children who might require developmental support services are not identified with the EDI. Since not all provinces/territories incorporate universal developmental screening in well-baby/child visits, many children who might require developmental support services are not identified. The research also suggests that relying on a physician’s impression would result in missing 45% of children who need early intervention.2

1Williams R, Clinton J, Canadian Paediatrics Society. Getting it right at 18 months: In support of an enhanced well-baby visit. Paediatrics and Child Health 2011;16(10):647-50.

2American Academy of Pediatrics. Eye examination in infants, children and young adults by pediatricians. Pediatrics 2003;111:902-7.