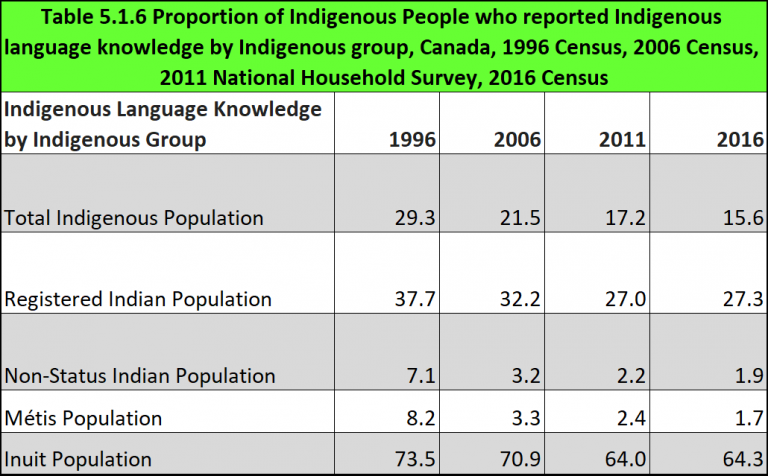

Proportion of Indigenous People who reported Indigenous language knowledge by Indigenous group, Canada, 1996 Census, 2006 Census, 2011 National Household Survey, 2016 Census

Notes:

1. Excludes census data for one or more incompletely enumerated Indian reserves or Indian settlements.

2. The total Indigenous population refers to the population that self-identified with one or more of the three Indigenous identity groups (First Nations, Inuit, Métis), and/or indicated Registered or Treaty Indian Status, and/or indicated band membership.

3. In 1996, 2006, 2011, excluded from these counts are respondents who reported more than one Indigenous identity, and those who reported being a member of a band with no Indigenous identity and no Registered Indian status. However, individuals included under these two groups reporting Indigenous language knowledge result in small numbers. In 2016 includes single and multiple languages.

4. The Registered Indian population refers to the population that indicated Registered or Treaty Indian Status.

5. The Non-Status Indian population refers to the population that identified as First Nations (single response) and indicated NO Registered or Treaty Indian Status.

6. The Métis population refers to the population that identified as Métis (single response) and indicated NO Registered or Treaty Indian Status.

7. The Inuit population refers to the population that identified as Inuk (single response) and indicated NO Registered or Treaty Indian Status.

8. The non-Indigenous population refers to the population that did not identify with any of the three Indigenous identity groups (First Nations, Inuit, Métis), did not indicate Registered or Treaty Indian Status, and did not indicate band membership.

Source: CICH graphic created using data adapted from Statistics Canada, 1996 to 2006 Censuses of Population and 2011 National Household Survey, Statistics Canada and AANDC tabulations. https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1377004468898/1377004550980 -accessed October 24, 2017 and Statistics Canada – 2016 Census. Catalogue Number 98-400-X2016160. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?TABID=2&LANG=E&A=R&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=01&GL=-1&GID=1341679&GK=1&GRP=1&O=D&PID=110449&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2017&THEME=122&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&D1=5&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0 -accessed October 30, 2017.

While the number of Indigenous people with knowledge of an Indigenous language has increased since 1996, the proportion has been steadily decreasing since 1996. In 1996 that proportion was 29.3%. In 2006 it had declined to 21.5% and in 2011 it was 17.2%. In 2016 it was 15.6%.

This decline may have been influenced by the increasing number of people who are self-identifying as Indigenous.

In 2016, 27% of the Registered Indian population had knowledge of an Indigenous language – down from 32.2% in 2006 and 37.7% in 1996.

Among Non-Status Indians, 1.9% reported knowledge of an Indigenous language in 2016. That was down from about 3% in 2006 and 7.1% in 1996.

In 2016, 64.0% of Inuit reported knowledge of an Indigenous language – that was down from 70.9% in 2006 and 73.5% in 1996.

In 2016, 1.7% of Métis people could speak an Indigenous language. That was a decline from 3.3% in 2006 and 8.2% in 1996.

Implications

Language is intrinsically linked to the development of strong cultural identity, at both individual and collective levels. It is important to a child’s mental health and well-being,1 to provide him/her with a sense of belonging and self-esteem as a foundation for individual resilience that contributes to the development of strong and resilient communities. In Canada, colonial legislation that aimed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream society has endangered many Indigenous languages. Of an estimated 450 Indigenous languages and dialects belonging to 11 language families, only 50-70 are still spoken in Canada, and only three (Cree, Inuktitut and Ojibway) are expected to remain and flourish in Indigenous communities.2 Language preservation and revitalization must begin in early childhood; “if the children of a community are not learning the language, the language will die out.”2

1Galley, V., Gessner, S., Herbert, T., Thompson, K.T., & Williams, L.W. (2016). Indigenous languages recognition, preservation and revitalization: A report on the national dialogue session on Indigenous languages. Victoria, BC: First Peoples’ Cultural Council. Retrieved September 12, 2017 from http://www.fpcc.ca/files/PDF/General/FPCC__National_Dialogue_Session_Report_Final.pdf

2McIvor, O. (2005). Building the nests: Indigenous language revitalization in Canada through early childhood immersion programs. Unpublished MA theses, School of Child and Youth Care, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC. https://dspace.library.uvic.ca:8443/handle/1828/686