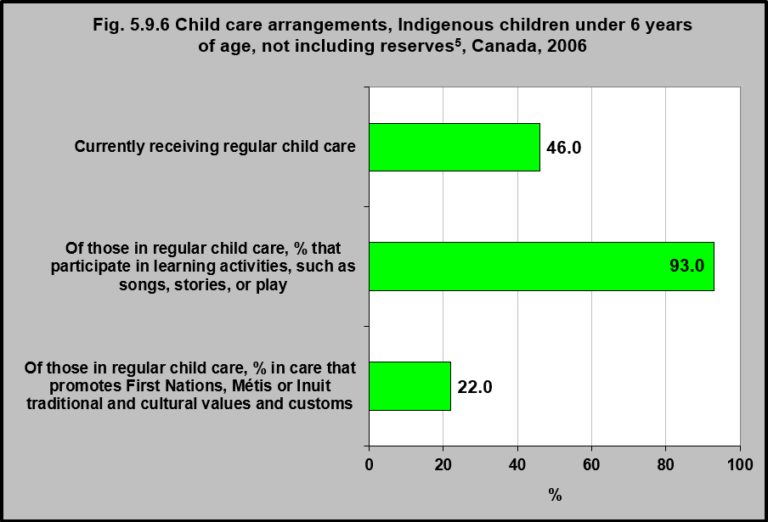

Child care arrangements, Indigenous children under 6 years of age, not including reserves, Canada, 2006

Notes:

1. Percents may not add up to 100 because responses of ‘don’t know’, ‘refusal’ and ‘not stated’ were included in the calculation of all estimates and rounding.

2. Excludes children who are currently attending school.

3. Child care arrangements refer to the care of a child by someone other than a parent, including daycare, nursery or preschool, Head Start, before or after school programs and care by a relative or other caregiver.

4. These data refer to the main child care arrangement; that is the arrangement in which the child spends the most time.

5. All Indigenous children in the Yukon and Northwest Territories (on and off reserve) were included.

Source: CICH graphic created using data adapted from Statistics Canada. 2006 Aboriginal Children`s Survey. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-634-x/2008005/t/6000040-eng.htm -accessed August 27, 2017

In 2006, of those in regular child care, almost all (93%) of Indigenous (First Nations living off reserve, Métis and Inuit) children under age 6 participated in learning activities, such as songs, stories, or play.

Only 22% of these same young children were in child care that promoted First Nations, Métis or Inuit traditional and cultural values and customs.

Implications

Learning about Indigenous languages and culture is critical for the development of a positive cultural identity, self-esteem and self-worth, which are essential for academic success and improving outcomes for Indigenous children. First Nations, Inuit and Métis children may not be exposed to Indigenous languages and culture in their homes; as such early childhood development programs and schools play a critical role in the transmission of Indigenous culture.1 Empirical evidence highlights the positive linkage between language, culture and health outcomes for Indigenous children which confer health benefits across the life course, including lower rates of suicide ideation and attempts, less substance use and depression, a greater sense of control over one’s life, and the transmission of values and practices linked to safe sexual practices and healthy relationships.1

1Ball, J., & Moselle, K. Contributions of culture and language in Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities to children’s health outcomes: A review of theory and research. Ottawa, ON: Division of Children, Seniors & Healthy Development, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada.