3.1.2 Status and Non-Status – Who qualifies for Status?

Source: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada website -accessed November 14, 2018.

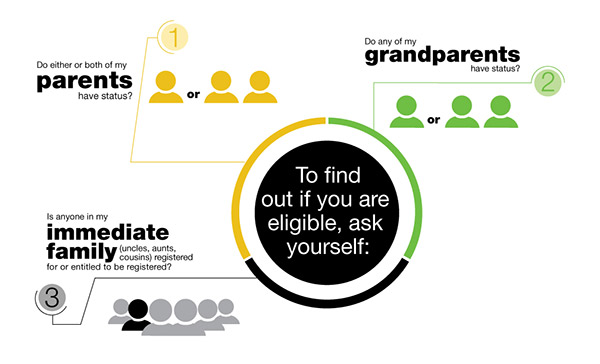

The 1876 Indian Act defines who is considered a ‘status Indian’. Registration for Indian status under the Indian Act in Canada is based on the degree of descent from ancestors who were registered or were entitled to be registered. For an individual to be eligible for status, at least one of their parents must be registered or entitled to be registered under subsection 6(1) or subsection 6(2) of the Indian Act or two parents are registered under subsection 6(2) of the Indian Act.1

A child of a non-Indian parent and an Indian parent registered under subsection 6(2) cannot be registered for Indian status.1

Anyone who is considered a ‘status Indian’ is eligible for programs and services offered by federal and provincial or territorial government agencies.1

Individuals who identify themselves as First Nations but are not entitled to registration on the Indian Register pursuant to the Indian Act are considered ‘Non-status Indians’.2

While there is no legal or legislative definition of “Métis,” they are recognized as one of three Indigenous Peoples under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. For the purpose of federal Parliament’s law-making jurisdiction under subsection 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, Métis and non-Status Indians are “Indians”; however, they are not eligible for programs and services currently targeted to ‘status Indians’.3

The relationship between Inuit and the Canadian government has been different than First Nations and Métis and is not related to ‘status’. In 1924, a bill was passed to amend the Indian Act, assigning responsibility for Inuit to the Department of Indian Affairs, but ensuring that Inuit would remain Canadian citizens. In 1939, the Supreme Court ruled that constitutionally, Inuit were classified as Indians in Canada. This distinction made Inuit the legal responsibility of the Canadian Government. Inuit are eligible for government programs and services.4

Although not eligible for programs and services targeted to ‘status Indians’ and Inuit, the government works with Métis and non-status Indian organizations, as well as with provincial governments where appropriate, to support initiatives for Métis and non-status Indians.2

In 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Métis and non-status Indians were “Indians” for the purpose of section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, and that the federal government had jurisdiction over them (Daniels v. Canada case). To date, there has been little progress on this ruling.

Based on the 2011 National Household Survey ‘non-status Indians’ represented 25.1% of the total Canadian Indigenous population, with three-quarters residing in urban areas.5

1Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada website -accessed November 14, 2018.

2Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada website -accessed November 14, 2018.

3Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada website -accessed June 15, 2018.

4Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. (2010) Canada’s relationship with Inuit: A history of policy and program development. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada. – accessed November 14, 2018.

5National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. (2013). An overview of Aboriginal health in Canada. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/context/FS-OverviewAbororiginalHealth-EN.pdf – accessed November 14, 2018.